Multi-Modal LLM Reasoning and Agent Modeling (B06-2)

Aaryan Agrawal, Nathaniel del Rosario, So Hirota, Zihan Liu, Trevan Nguyen, Samual Zhang, Zhiting Hu

Overview

A good agent must efficiently automate tasks across various domains, adapting like a human rather than relying on rigid, predefined rules. Traditional heuristic approaches, such as scrapers or task-specific scripts, struggle with unpredictable web environments, failing to generalize beyond their intended use cases or recover from unexpected errors.

Motivation

Large language models (LLMs) address limitations of traditional heuristic approaches in unpredictable environments by leveraging textual and structural web data, allowing for more flexible decision-making through exploring the Tree of Thought. Unlike static heuristics, LLM-based agents can reason dynamically and handle open-ended tasks. Additionally, scaling computation improves their performance, though determining the optimal way to do so remains a challenge.

Methods

LLM-Reasoners

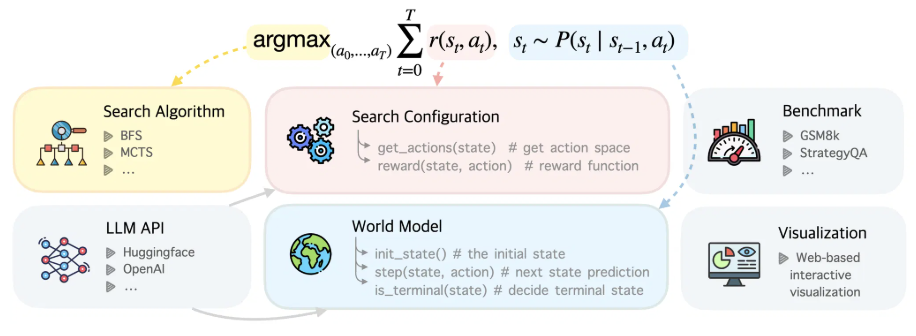

LLM-Reasoners is a standardized, library for creating reasoning agents with a modular framework for customizing the LLM, search algorithm, search configuration, world model, and benchmark architecture. We leverage LLM-Reasoners to investigate this behavior in Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) scaling experiments.

- Figure 1: Custom Agent Architecture via LLM-Reasoners

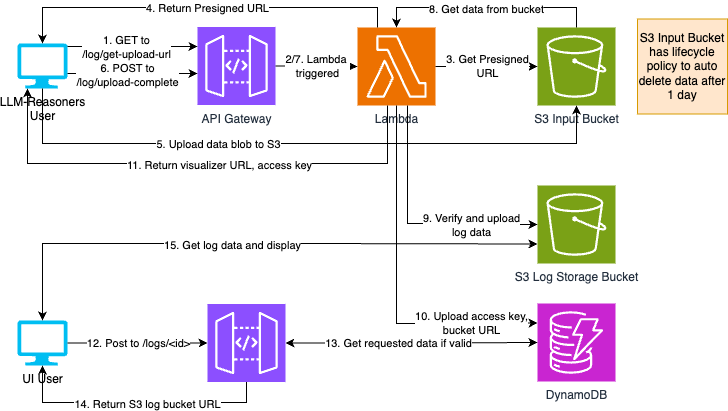

- Figure 2: LLM-Reasoners visualizer architecture

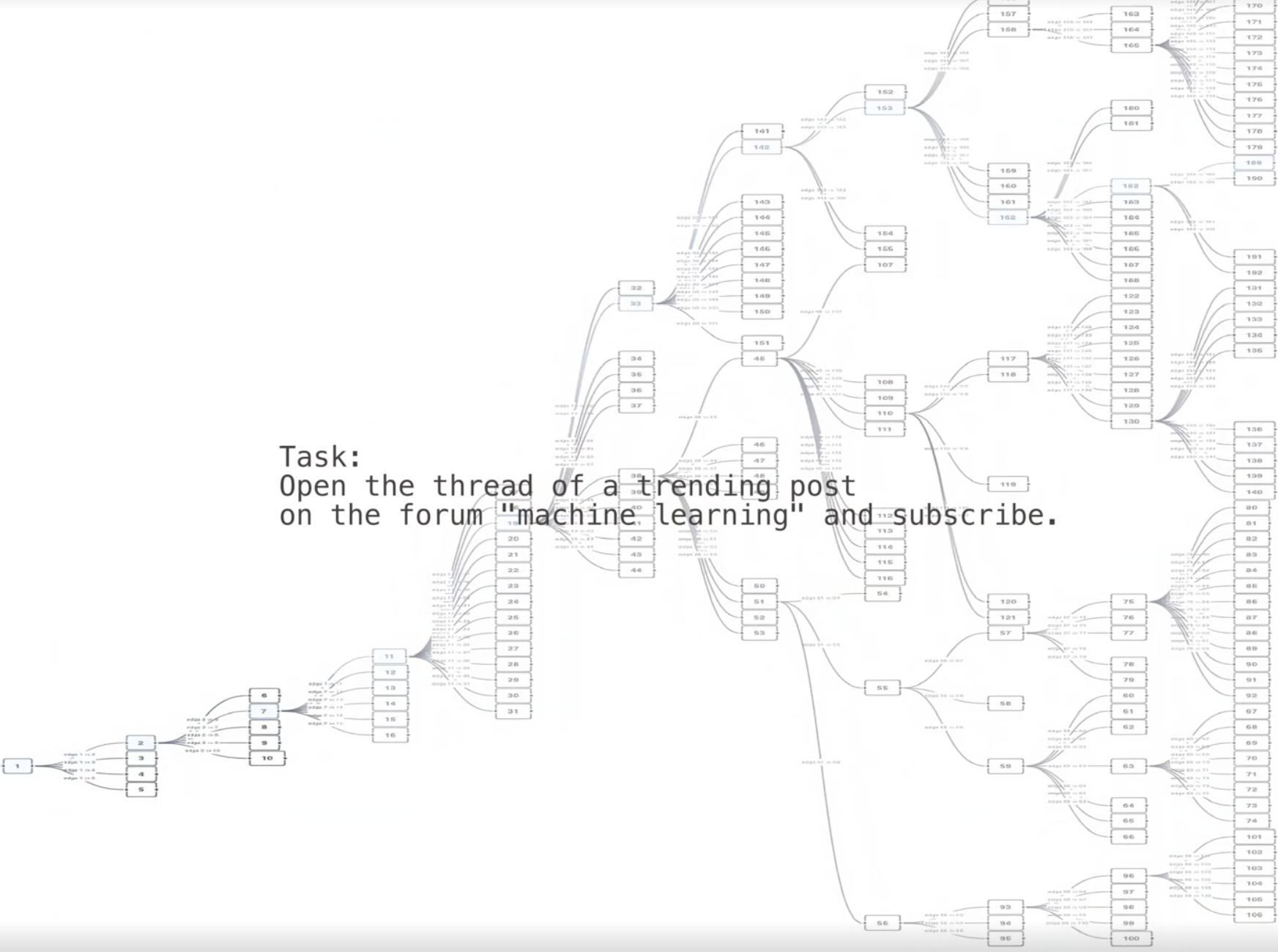

- Figure 3: MCTS Tree via LLM-Reasoners visualizer

BrowserGym

BrowserGym is a web-based environment designed to evaluate web agents, functioning similarly to OpenAI Gym but for browser interactions. It processes actions as JavaScript code executed via Playwright, though to simplify the action space, predefined functions (e.g., click, fill, go back) are used to mimic human-like interactions with a keyboard and mouse. Observations returned after each action include the page’s HTML, accessibility tree (AXTree), and a screenshot. However, due to the excessive noise in raw HTML, only the AXTree is passed into the LLM context. Screenshots are also augmented with a Set of Marks (SoM) to improve grounding for LLMs.

OSWorld

OSWorld is a desktop environment for evaluating agents on operating system benchmark tasks such as Chrome, VSCode, Gimp, etc. To complete a task, a web agent must take multiple sequential actions. Errors in later steps can make a task irrecoverable without backtracking. Two primary approaches to search are considered: implicit search, where the agent itself attempts to recover from mistakes, and explicit search, where a structured algorithm like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) assists in decision-making.

- Figure 4: Example OSWorld Task - “Change the default Search Engine”

Implicit Search:

Agent attempts to correct its own mistakes through direct actions, such as clicking an undo button.

- Fast and computationally cheap.

- LLM handles recovery but often fails in complex scenarios.

- Equivalent to single-iteration MCTS with no accumulated visitation statistics.

- Incorrect recovery steps may lead to further failure

Explicit Search:

Uses MCTS & LLM prompting/self-evaluation to guide back-tracking and exploration, leveraging cached states and structured rollouts.

- More reliable, structured decision-making.

- Computationally expensive due to multiple rollouts and evaluations.

- Requires assumptions about the ability to backtrack

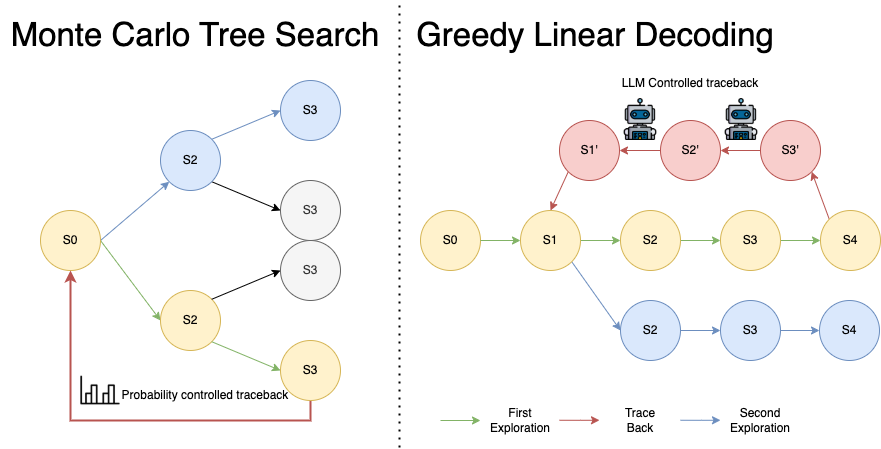

- Figure 5: Test Time Scaling

Results

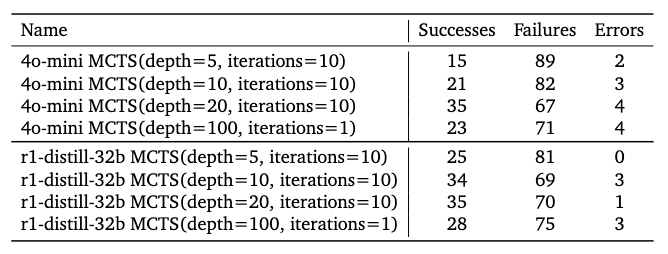

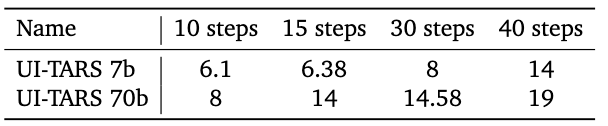

Implicit vs. Explicit experiments were conducted on a subset of 106 / 50 tasks from the WebArena & OSWorld benchmarks using GPT-4o-mini and UITARs 7B / 72B respectively

BrowserGym

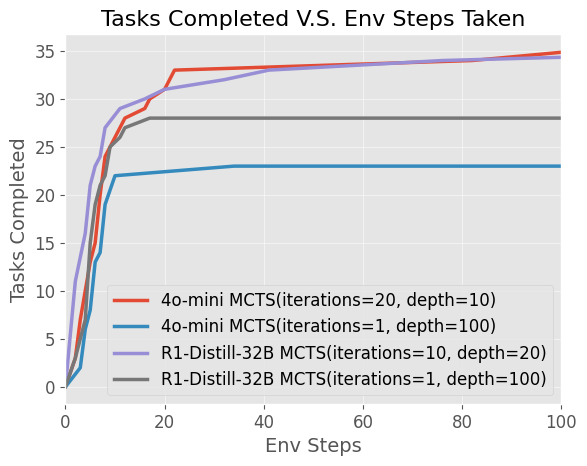

In summary, the R1-Distilled-32B model performed substantially better than both 4o-mini and 4o, and in general task success saw an increased correlation with the number of MCTS iterations and depth.

- Figure 6: Success Count with Different MCTS Parameters

- Figure 7: Explicit Environment Comparison

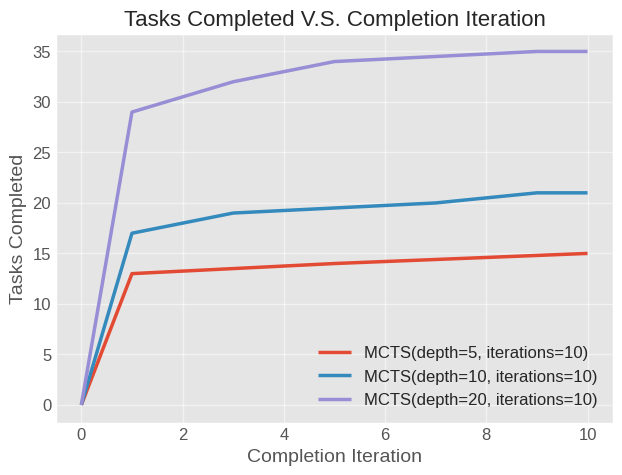

- Figure 8: Tasks Completed v.s. Completion Iteration

OSWorld

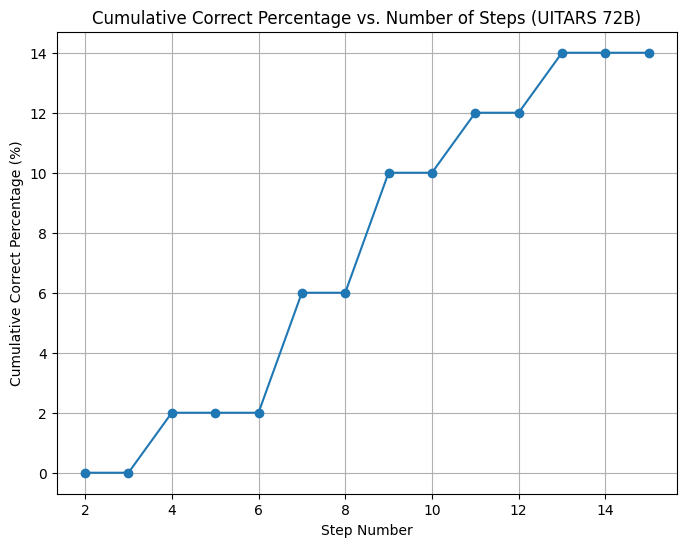

In summary, the UITARS-72B model performed substantially better than both 4o-mini and 4o, and in general task success saw an increased correlation with the number of MCTS iterations and depth.

- Figure 9: Depth of N Scaling

- Figure 10: UITARS-7B through 15 Steps (no MCTS)

- Figure 11: UITARS-72B through 15 Steps (no MCTS)

Discussion

Scaling Considerations

Token Usage & Cost The total cost of the experiments was $44.63 USD, with a full dataset evaluation on GPT-4o estimated at $5,355.60 USD, making large- scale runs prohibitively expensive. Token usage increased significantly with search depth, with cached prompt tokens helping to mitigate costs. Execution time closely followed token consumption trends.

Explicit Search on Environment Performance improves with increased itera- tions and depth, as seen in Figure 7. Greater depth allows agents to correct suboptimal actions, increasing task success rates. However, most successful completions occur in early iterations, suggesting that while iterations help, depth is the more crucial factor. Failure cases tend to max out iterations, indicating that being stuck in a poor search space is a major issue

Evaluation

Web/OS-based agents using LLMs show promise in automating browser tasks, but scaling inference efficiently remains a challenge. This work explores the question of how best to structure search: implicit (greedy, depth-limited) or explicit (structured exploration like MCTS). Implicit search is potentially computationally cheaper but struggles with backtracking, while explicit search enables efficient exploration but relies on resettable states, which may be impractical in real-world web environments.

Experiments on 106 WebArena and 50 OSWorld tasks show explicit search achieves higher task completion rates and better environment interaction efficiency. While explicit search excels in controlled settings, implicit search remains more applicable to real-world tasks. Another aspect to consider is conducting an explicit search on an LLM world model, where the search occurs over predicted next states as opposed to the environment itself, which can potentially gain the benefits of both implicit and explicit search.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to our advisor, Professor Zhiting Hu, and his two PhD students, Zhoujun Cheng and Shibo Hao

References

See our formal report.